Helping a child learn to read is a unique pleasure. Seeing their eyes light up when they pronounce their first words can be heartwarming and rewarding. Getting there takes work — and patience. The reading journey begins when children are very young — even in the womb.

PRE-NATAL

Children learn patterns of language even before they are born. Research shows that babies who are read to in the womb have greater brain activity. “Talking and singing with your baby and reading with your baby even before birth can be a way to foster early social interactions and even later learning,” writes Tricia Skoler Ph.D., for Psychology Today. Skoler recommends familiarizing yourself with your local library and even getting your child a library card before he’s born. Children recognize their parents’ voices in the womb, so reading every day to your unborn baby will help form a bond with your child.

THE FIRST YEARS

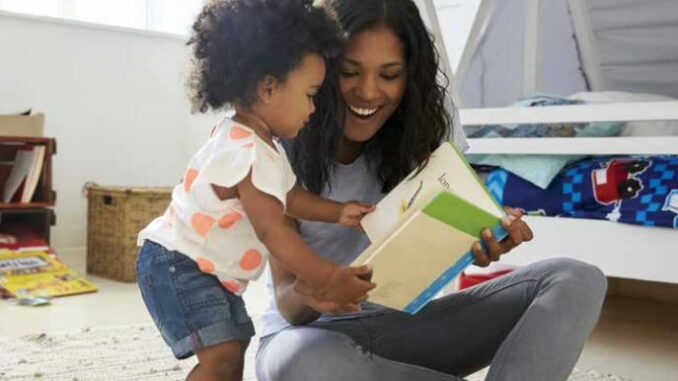

After baby arrives, you should try to weave reading throughout your day, Skoler writes. Squeeze in 10 minutes here and 20 minutes there, working up to 30 to 60 minutes a day by the time baby is 4 months old. Having caregivers read to the baby, as well, will help enhance the experience, as babies need to be exposed to different reading styles. Having extended family members read to the baby when they visit also helps build relationships.

PRESCHOOL

Preschool is an exciting time for young learners, as they begin to make rapid progress toward reading and writing. By preschool, children need lots of exposure to written and spoken language to advance their reading skills. “Kids need to understand that things you say can be written down,” said Georgia Kent, a reading specialist in Lake Zurich, Ill. Write shopping lists with your child and talk to them about what you’re doing any time you’re writing can help a child form those connections, she said. Exercises as simple as pointing out the first letter of a store name on a sign can help children understand phonics, Kent said.

For example, point out the T in Target or the M on the McDonald’s sign. The “language experience approach” is a way of using a child’s own experiences to help them learn about writing. You might ask your child, “What did you do today?” Then record his musings about his day and read them back to him, pointing out each word as you read. This helps expose children to many aspects of written language, according to Kent, such as the fact that text is read from left to right, there are spaces between words, and the importance of the first sound in each word.

Another useful exercise at this age is to “stretch out” words and point out each individual sound. You can even create a sound box, a visual representation of how a word is put together. Draw each part of the word in a separate box, then move a bead, a bean, a penny or any other small object from box to box as you sound out the word.

A NEW READER

Once your child can read on his own, it’s tempting for parents to stop reading to their child — but don’t. It’s still important for children to have reading modeled for them, and it will increase their enthusiasm for reading. Knowing your child’s reading level can help you guide your child toward books that are appropriate for her ability. Ask your child’s teacher which reading scale the school uses (there are a handful) and where your child is currently performing on the scale. A librarian at your public library will be able to help you find suitable books. Be sure to let your child be involved in choosing from books at her reading level. This will make her more likely to read for enjoyment.